By Richard Thomas

In American whiskey circles, few if any companies elicit the same level of suspicion as Templeton Rye. Take the company’s recent marketing exploit in turning their spent mash grain into hog feed to create “whiskey pigs.” The claim was met with a storm of derision in the blogosphere, with some questioning whether the grain in question was even the same as that used in Templeton’s sourced whiskey (it is).

To some, that violent skepticism might seem like an overreaction, but to others Templeton’s “whiskey pigs” gimmick is just another example of the company’s dodgy marketing. After all, there is nothing special about turning spent mash grain into animal feed. Most distilleries in Kentucky and Scotland do it, and have been for decades. Also, the notion that this feed imparts any whiskey flavors to the animal is ridiculous, something I can personally testify to, as I came of age with a toe in Kentucky distilling and a full foot in Bluegrass animal husbandry.

Yet dodgy or not, the “whiskey pigs” were a roaring success for Templeton Rye. Four months later and I still periodically see credulous tales of whiskey-flavored pigs in Iowa appearing in my news alerts. This combination of loose-but-successful marketing is typical of Templeton Rye, and the source from which that aforementioned suspicion flows.

In this first installment of our series on claims against deceptive whiskey practices, The Whiskey Reviewer tackles Templeton Rye. The case against the whiskey company will be assessed in four categories, each analyzed and graded on a four-point scale, similar to the American grade point average. Those separate scores will then be averaged, and a overall grade affixed to the entire case.

The Case

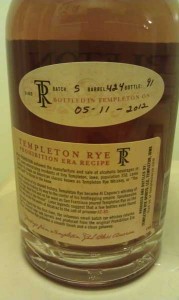

Potemkinism: Conventional wisdom has it that Templeton Rye is the archetype “Potemkin distillery,” meaning they are a bottler that claims to be a distillery. According to the most frequently repeated version of the story, Templeton spent years denying the fact that their whiskey was 95% rye stock from LDI/MGP, the industrial distillery in Indiana, while claiming it was made by them to a bootlegger-era mashbill.

As is usually the case, the conventional wisdom is not entirely accurate. The fact is that Templeton Rye’s origins have been established since at least 2008, and also for at least that long the company has been frank with inquiring journalists and bloggers about where their whiskey comes from (some of them were not as obliging about communicating that information on to their readers).

The company never flat-out denied the fact that their whiskey was made in Indiana, but instead tried to obscure it behind a veil of stories about the Templeton rye of the 1920s and 1930s. In other words, the official version differs markedly from the sales version of the story. Early versions of the company website avoided the sourcing issue altogether, and current versions still cloud the issue of whether the LDI/MGP whiskey is the sole source of the stock product.

Another part of the usual story that isn’t true is that Templeton isn’t a distillery. They have been making their own juice for several years now, although none of that has found its way into their regular product. (Grade: 4.0 — A+)

Back Story: The case against Templeton Rye raises two historical issues. First is the use of a bootlegger mashbill, as claimed in Templeton Rye’s literature. The company may very well be making a whiskey using such a recipe, but as we have seen, it isn’t the whiskey that comes in Templeton bottles, and they weren’t always particularly upfront about that.

The other historical issue are the allegations made by some that there was never any such thing as genuine, bootleg Templeton rye whiskey, or that if there was any bootlegging in Templeton it was just moonshine. Those claims were false, as anyone who bothered with just a little Googling would have soon discovered. Now there is even a well-researched book on the subject of Templeton, Iowa bootlegging, and yes, Al Capone liked Templeton’s juice. (Grade: 3.0 — B)

Marketing Flim Flam: While not strictly speaking a falsehood, Templeton’s current “whiskey pigs” publicity stunt is certainly an exemplar of very slick marketing. (Grade: 3.3 — B+)

Changed Ways: The problem with Templeton Rye is that they always seem to have two stories. Although they generally admitted to sourcing their whiskey in private, their public story was very different. Those two stories have gradually come closer together over the last several years, but they are still more or less separate. The company could have laid claim to Templeton’s bootlegger heritage without going this route, using only somewhat different language. (Grade: 3.4 — B+)

Overall Case Grade Against Templeton Rye: A-

Summary: Although not free of blemishes, the case against Templeton Rye is a strong one.

Something revealed in the previously cited book, Gentleman Bootleggers, is that the real bootleg Templeton rye was unaged and small barrel whiskey. Although this was not the case when Templeton Rye got started in 2006, many craft distilleries have emerged since that have used a mix of white whiskey, small barrel whiskey, and bottled products to establish their brand name. The sad conclusion that comes from knowing those two things is that it’s not hard to see how the company could have better lived up to its billing. Instead, it has become a stereotype for deceptive whiskey marketing.